take it to the streets

I was in the neighborhood of my kid’s elementary school some weeks back with my preschooler, on a day that border patrol agents had released tear gas near another school a few neighborhoods away, and so I decided to do a few laps around the block. The kids were out at recess, and I had a whistle, so I knew that if I saw ICE or border patrol agents I could alert the school to rush kids and staff inside.

The thing about tear gas is that we all breathe the same air. When we’re on the same block, and tear gas has been deployed, it’s in the air you’re breathing just as it’s in the air I’m breathing. This is possibly an inane thing to say, but I’m not sure we all really get it deep down. Some border patrol agents last week got stuck in their own tear gas cloud and had to abandon their vehicles and leave on foot, so at least they don’t seem to understand it, they who deploy the canisters “for fun” (their words).

This is a basic principle of antifascism well-illustrated by our enemies. You can’t make an enemy out of everyone because at a certain point, you’re poisoning your own air. We all live on this planet, and if we kill it, it’s the end of us. We all depend on this vast living web and if we break its connections, there’s nothing for us to eat. We all need each other as social beings and if we tear at the social fabric, if we ruin our ability to be in relationship, then we’re dead alone.

But these things are easier to forget when the violence is abstracted and hidden away. If tens of thousands of people are dying needlessly because of denied or delayed health insurance claims or lack of access at all, sometimes we forget this is murder. It feels instead like an unpleasant normal milieu that is sometimes more personally painful to be in. If a million people are murdered with bombs and bullets just because of where they were born, but it happens around the world, to those we’ve swallowed dehumanizing stories about, sometimes we forget those are people. It feels instead like a nightmare of some kind, a Grimm fairy tale.

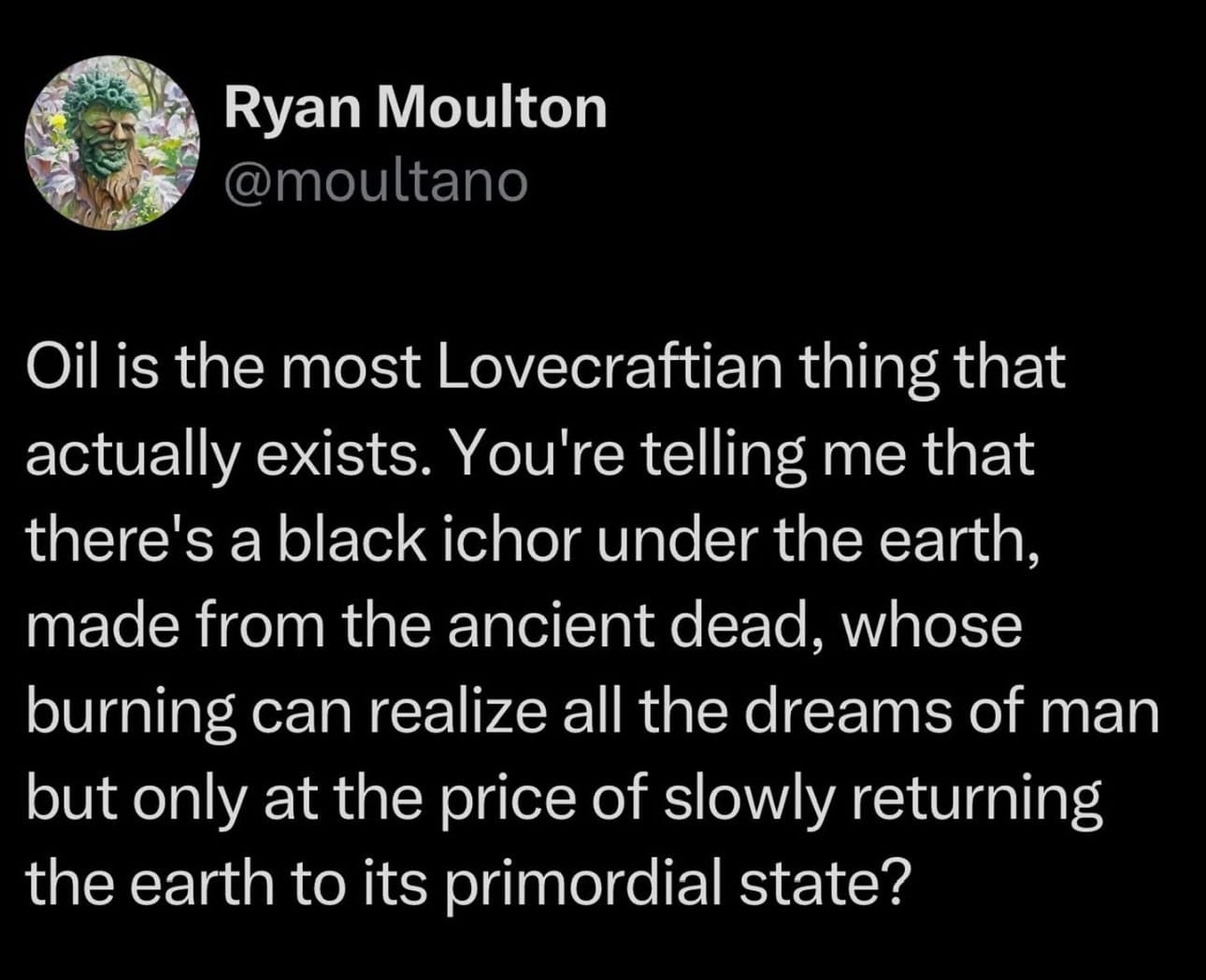

And yet, real people die. We get more and more unhealthy. Children go hungry. The oil people have killed and profited over keeps getting dug up and put in our cars. Some drops of it used to be a specific alive creature millions of years ago. The cars kill raccoons and deer that try to cross the road, who probably feel terror in their last moments.

The imperial boomerang is a concept described originally by Aimé Césaire, who noticed that the horrific violence of European fascism was only unprecedented if you forgot people existed elsewhere, if you didn’t count the victims of European colonization. An imperialistic state entity motivated to technologically murder people won’t do it first to its own citizenry, but once they can get away with it, certainly they will. What happens elsewhere will happen here too. The imperial boomerang returns, so if we care about our own skins we should care about where the boomerang goes and has gone.

I grew up in a house where the imperial boomerang perpetually returned. American bombs dropped on the other side of the world had gone off and echoed in family members’ memories, in the attachment figures missing, in the loss and despair and hypervigilance and relational pains that result. A commonplace severance struggled to take hold in me, because I had a front row seat to the consequences of our foreign political violence.

Learning about politics and the big picture of violence and immiseration – and the social configurations like capitalism, racism, the patriarchy which create them – always felt like a way to understand the particularities of my family’s life. The big picture explained my little picture, and the little picture corroborated everything I heard about the big picture.

I think you’ve likely had an experience like this too. You’ve had a little picture experience, and then you’ve learned more about how the world works, you’ve heard from others that have had a similar experience, and you’ve realized how deeply your experience wasn’t an isolated particularity but rather a consequence of the way we all live our lives.

It’s just that once we start to pay attention, we see that the sky is falling, and we know that even if it crumbles elsewhere first, it’s all coming down. Boomerang after boomerang launched – we have known they are going to come back around.

You just can’t take and take and take and expect the back you are standing on not to crumple. You just can’t make enemy after enemy after enemy and expect someone to be there to hold your hand at your bedside.

There are a lot of ways for the big picture and the little picture to collide, which is another way of saying there are a lot of ways for us to have a felt sense of the threads that connect our particular worlds (in all their rich and excruciating and exquisite details) to the great big one (blanketed in one beautiful sky that wraps us all up in it).

People are needlessly dying because billionaires exist, the planet is being killed, the bombs are dropped – not only is this real but also it is a consequence of the political structure we are mired in, which must be destroyed. The longer it takes for us to understand this, the less likely we are to make it. But it’s so difficult to destroy something that abstracts itself away from us, and then only enters our lives to hurt us, insidiously, through deprivation or intervention long gone.

Ah, but here it comes, the boomerang returned, the sky falling here too: I live in Chicago, target of Operation Midway Blitz. Agents don the aesthetic of violence and get in their flashy American-made SUVs with heavily tinted windows in order to abduct my neighbors from the sidewalk. They enter daycares and do it in front of children. They tear parents from their babies. They shoot and kill.

My enormous fear was that Trump would massively accelerate the impoverishment con machine of capitalism via fascist scapegoating and that we would do nothing. That people would freeze, or watch the courts fail to fix it, or just go about their lives continuing to pretend that prisons and concentration camps didn’t exist.

But that’s not what’s happened at all. Chicago is under occupation, and the fight against fascism is in the streets now. Our enemies’ actions aren’t abstracted or hidden away from us in this instance: they are right in front of us as we go about our days. And we are meeting them there.

The streets of our city, part of our commons, are where we have always been able to meet each other, come to know the particular details of each others’ lives, the little pictures that corroborate a big picture we are coming to understand. They are places where we can intervene for each other. I’m glad that, now that they’ve brought the fight to the streets, we’re going there to meet them. I’m glad that something in us responded once the mask came off, once the boomerang returned.

The distance between the decision to organize our society suchly (racialized capitalism, hierarchical immiseration, etc) and the consequences of that organization is shortening: no more convoluted mental gymnastics to get us out of the awareness that we all breathe the same air.

That day that I patrolled around my kid’s school with my preschooler, I was anxious. I wanted to keep a lookout, to pass out some whistle packs, to warn the vulnerable people I could that ICE was in the area, and to get in the way of their terror if I had the opportunity. But my preschooler was in the backseat. They’ve assaulted, detained, and otherwise terrorized rapid responders who intervene.

I waited at a sandwich shop for our lunch order, watching the cars out the window while trying to prevent the kiddo from strewing a fistful of straws on the floor. Soon somebody else entered the cafe with a whistle around their neck. And then a few more people stationed across the street. And some others at each of the neighboring intersections. I chatted briefly and exchanged names with my fellow sandwich shop patron, and said I was thinking I’d go home and put the antsy kid down for a nap. “It’s okay,” she said. “We got this.”

Something similar has happened several times since then. I respond to a call and I meet friends there. I ignore the messages and find clusters of people on the corners, whistles around their necks – strangers and neighbors and parents of my kids’ friends. I nod at bikers chasing caravans. I get in line behind someone else visiting the same coffee shop on the same targeted block for the same reason. I show up to the meeting and there’s standing room only.

What a comfortable place to be, I keep thinking. I’m terrified and exhausted, but what a comfortable place to be, in this city where so many respond, where a fight taken to the streets takes us there too, spontaneously and independently and collectively. Maybe, on the other side of this, however long it takes, we will all take to the streets but only for different reasons, to dance and sing, or have a parade, or because it’s a mast year and acorns flood the gutters. Or just to be together in this comfortable place.