grief bigger than I am

(this was originally posted over on my substack in Feb 2025, but I'm migrating it over here)

I’ve spent a lot of time lately trying to fathom unfathomable things, like wrapping my arms around the earthbound end of a redwood trunk. I know it can’t really be done, but I don’t know how to move forward without trying. The truth is that I see on the horizon a lot that really scares me, and it’s hard to imagine getting through it – so I’m trying to imagine it (because I’d like to get through it).

When I reflect on this, a lot of what comes up is grief. Grievous grief. There’s so much suffering ahead of us, and a lot behind us too, and a lot in our present. Tens of thousands of people in Gaza have been killed by Israel and its fascist Zionist project (reliable estimates indicate likely more than 100,000), and Gazan Palestinians have just finally received enough of a reprieve that they can return home, start to mourn. Meanwhile, Trump and his fascist party are creating concentration camps for refugees who came here seeking safety from American-backed violence and instability in their homelands. The right-wing attack on trans people is escalating to horrendous proportions.

How do we wrap our arms around this? I know that we must try, because if we can’t grieve what we have lost or might lose, then we can’t be moved to defend it. Is life precious to us, or not?

I was at the Field Museum recently with my toddler, who wanted to visit the dinos. We headed towards the current exhibit housing Sue, the Field’s famously near-complete T.Rex skeleton. We were welcomed by a TRex figure with half of some other poor dinosaur in its mouth – this freaked out my toddler, who thinks of dinosaurs not as prehistoric more-or-less mythical predators, but rather pets and friends they haven’t met yet.

This is an aside, but there are so many access points for the industry of dinosaur fandom. You can get cute dinos that are your friends, you can be a special-interest dinosaur fan who knows all the scientific names, you can be into dinosaurs because they are reptilian and vicious.

The Field Museum was leaning into that last one, and my toddler didn’t know what they were getting themself into. I didn’t exactly either, even though I’ve walked through the exhibit before, which is set up as a tale of mass extinctions.

- Mass extinction #1: about 445 million years ago, global warming, or maybe global cooling, or maybe volcanoes and resultant lack of oxygen, kills off 85% of all species

- Mass extinction #2: between 359 and 372 million years ago, through a series of events a million or more years apart, 70% of species on earth are killed

- Mass extinction #3: 252 million years ago, “The Great Dying”; trilobites don’t make it.

- Mass extinction #4: 201 million years ago, 75% of species die, leaving dinosaurs with little competition

- Mass extinction #5: 66 million years ago, a massive asteroid hits the earth. None of the non-avian dinosaurs make it. Mammals, soon after, have their heyday.

In the face of all this, it almost feels obscene to advocate for my little circle of life in particular.

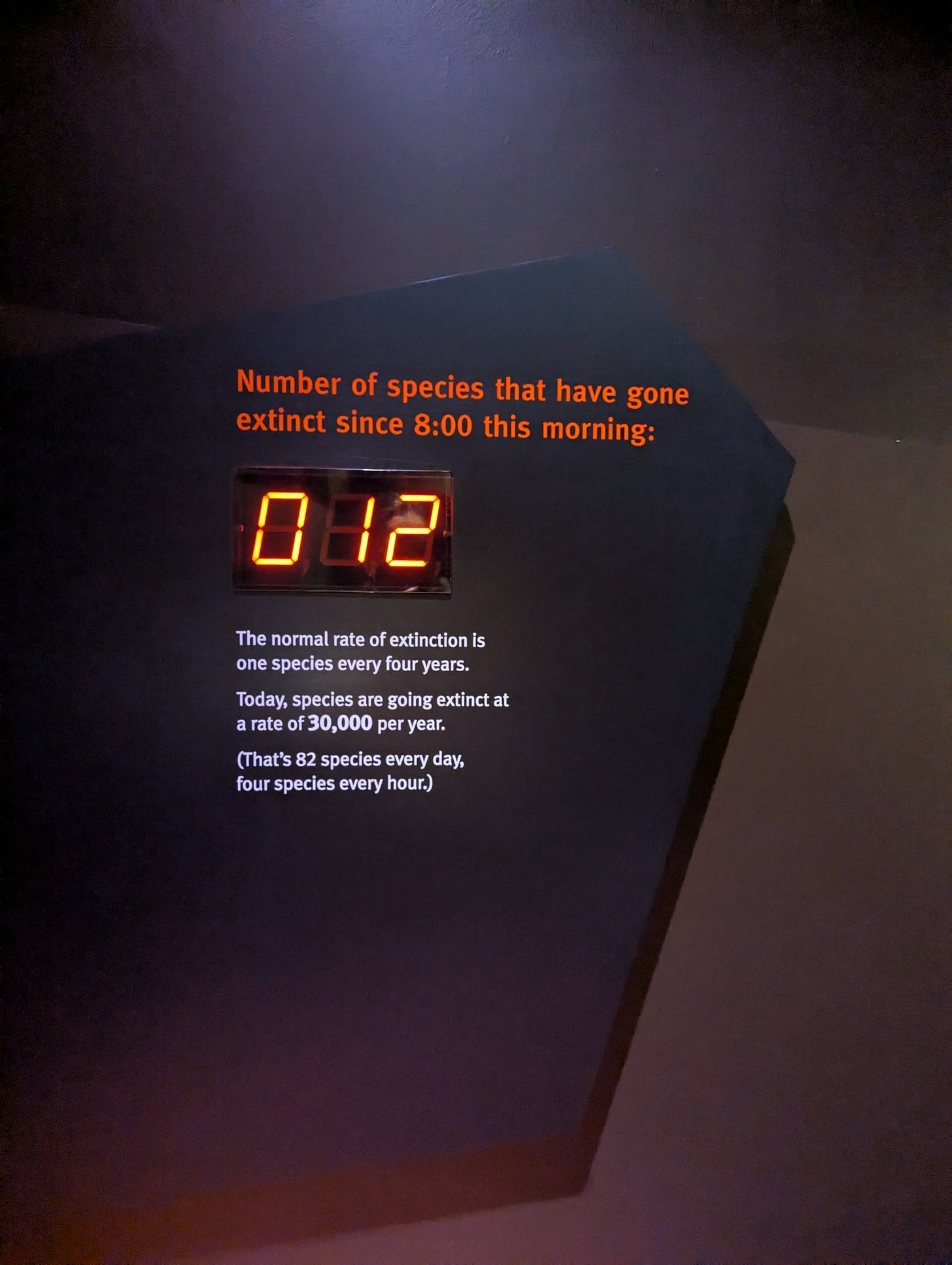

At the end of the exhibit, there’s one wall, just a panel really, titled “Mass extinction #6”. This is of course the one we’re in right now. It contains three elements. First, a short paragraph on human-caused mass extinction. Next, the preserved body of a trumpeter swan, a species now extinct – the swan is shrouded, its head bent back against its body. Finally, a screen displaying a bright orange 12: the estimated number of species that have gone extinct since 8am this morning. When I visited it was just after 11am..

After this portion of the exhibit, you enter directly into the gift shop.

I’m not sure the effect this is supposed to have on me. Should I become numb to all this mass death, brush it off because it happened millennia ago and to ancient creatures I can’t relate to and which scare me? It’s hard to make sense of this epic scope of death in mass extinction after extinction. But I do think the museum is trying to dignify all these dinosaurs. Sue, our famous T Rex, is depicted as a vicious and terrifying predator. But we’re told about how she died in her old age. We’re oriented to the massive knobs of scarring on her bones that indicated she’d suffered and healed serious injuries. We’re invited to smell her breath and imagine the scene of her dying. (In the cafeteria, they sell dinosaur chicken nuggets.)

So what will happen to us, or all those living around us? We’re living another mass extinction event, and so I wonder about what it was like to live those other ones. I know that something survived, each time – life didn’t have to evolve itself from scratch. We’re going through a mass extinction, and if we’d like, we can hope that we’ll make it. Of course, if we hope we’ll make it – if we hope anybody makes it – we should expect that hope lives through us as action towards ecological care and protection, towards going up against this human-caused destruction.

These begged questions about who is gonna make it, and how – they always lead me back to the small scale, to my own little life. My loved ones and what might happen to us. In particular, of course, our children: who inherit this place, who (we pray) will outlive us, and will see more of what’s on the horizon than we will. I think about the pragmatic realities of living life now and in the near future, the things I want to do to prepare my children, to set them up for resilience and connection and an ongoing struggle, to leave them connected in a world that they love and which loves them back.

A friend talked about the experience of kaleidoscoping awareness in these times. I see the giant numbers, millions of years, so many species – a cylinder turns, new colorful crystals come together and the same light goes through it – I see the number twelve, the soft feathers of the swan. When we are zoomed out enough to consider the real, honest scale of suffering that’s happening right now, we actually can’t fathom it truthfully if we’re not also zoomed in – numbers on a page (casualties, orphans, injuries, species extinctions, degrees of warming…) are relevant, but we don’t have the whole picture if we aren’t also real about those numbers being people, beings, places that are as real as our own children are real to us. And when we know reality in this way, we are invited into massive grief.

So I left the Field Museum a bit stunned, with the feeling I was trying to wrap my arms around a redwood. Or maybe I should say around a titanosaur’s femur (those things are massive). The rest of the week I kept kaleidoscoping. One evening I found myself on the wikipedia page for the 1918 flu epidemic. Maryn McKenna on bluesky had discussed how little it was memorialized, and how that’s affected us today. If we hadn’t been stunned by the caterwauling horror of World War I, maybe we could have grieved our lost. Maybe things would’ve been different when the next big pandemic came along.

That rabbit hole soon led me to the Bubonic plague which was estimated to have killed 50 million people in the Black Death. Whole families wiped out. Mothers burying all their children.

Mass death is here now too, swooping in and out of my own circles, in and out of our collective stories, touching us in the imperial core and then being pushed out of awareness.

In the face of mass death, what are we to do? How do we get through it? How do we accept it?

A few years ago, if I had been posed these questions, I would have turned away – we shouldn’t accept mass death, I would’ve thought. That’s not an outcome I can accept. We need to put our heads down and focus like we haven’t ever before on the project of preventing these horrible outcomes.

But I don’t mean accept as in invite. I don’t mean accept as in let happen. I mean accept as in: this is reality. Mass death is upon us, around us, in our very near past and our current moment and the future that’s rapidly approaching from the nearest horizon. 30,000 species every year.

I don’t believe we can really come to know what it is we must do to save each other and ourselves and the children if we don’t face this reality. It’s an unacceptable horror, but it’s also reality.

We are in the throes of the grievous dialectic: two truths pull, hard, against each other. First, the more we come to know the scope of horror, the more we know it to be one that will break us, stop us in our tracks, terrorize us. Second, we cannot prevent more of this horror without getting real about what’s going on.

A tension like this often leads us to see-sawing emotionally, to taking turns renting our garments and going numb, or telescoping in our vantage points. But with connection, support, and time, our minds and bodies can find a place of walking along the tension of this dialectic instead. I think Samuel Beckett said it well: “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.”

So if we have entered a long period of darkness, and if we can accept this, then what are we to do? I came across an excerpt from Francis Weller (a psychotherapist specializing in grief), quoted by Holly Truhlar in this post, which described the dark as a place of mourning and necessary decay, and a place in which we can find positionality and intention and agency. We must “operate under the possibility that something might sustain” (just like life survived the first five mass extinction events), we must become places of safety and refuge for each other, and we must “throw as many seeds as possible into the darkness.” This is how we orient ourselves so that we can become “a place of shimmering darkness … of incandescence.”. It felt like kismet when just a few days later the Bengsons released an extraordinarily moving song called Echolocation about finding each other in the dark, and calling for dawn.

hollytruhlarA post shared by @hollytruhlar

Finally, there was something else I was reminded of this week: the dark ages, those famed times of the plague – we so often think that they are called the dark ages because they were before the Renaissance, the supposed time of enlightenment in which Europeans began to know things and life really started for them. We imagine that the people in the Dark Ages lived lives that were grey and dimmed, missing in vitality or interest, dull. But that historical period is called Dark because of the scarcity of documentation from which we might learn about it. It’s just dark to us. We don’t know what it was like to live it. Surely, there was immense suffering. It was dark, in that sense. But maybe that dark became an incandescent site of life. Maybe it shimmered.